As an industry, electrical lighting is relatively new—less than 150 years old —and it originated thanks to an entrepreneur. This individual conceived of electrical lighting as a process of busy, active thought, contemplation, deliberation, experimentation and invention. His name is Thomas Edison.

Edison founded what you see today as the American lighting industry.

Much has been written, said and depicted about the legendary inventor of the incandescent light bulb, yet his prosperous and enduring business and industrial history is not as well known.

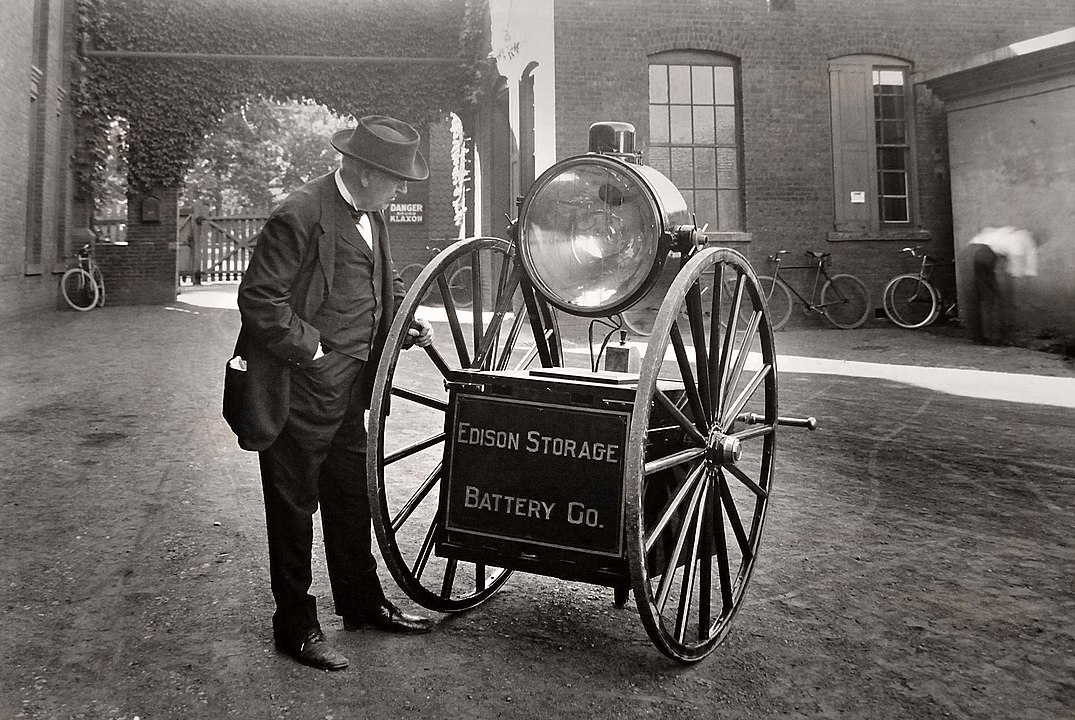

In fact, Thomas Alva Edison, born half-deaf in America’s Midwest and a newcomer to New York City, who later forged a laboratory in New Jersey, founded the Edison Illuminating Company on December 17, 1880 and the Edison Battery Company on May 27, 1901, to develop, manufacture, and sell the Thomas A. Edison light bulb and the Edison Storage Battery.

How did Edison manufacture the light bulb for mass market distribution? How did Edison run his company? What were his thoughts on competition?

Self-made and self-educated Edison, born to poverty in Michigan, got his first job at the age of 12. Before becoming a serial inventor, he was a newsboy. Fascinated by telegraphy, according to the PBS documentary, he started working with a telegraph company at 15, tinkering with machines. Here, Edison learned the basic principles of electricity. He embodied the spirit of entrepreneurship and American ingenuity that fueled so much of the Technological Revolution of (1850-1914); clever, inventive, sometimes impulsive, driven to succeed.

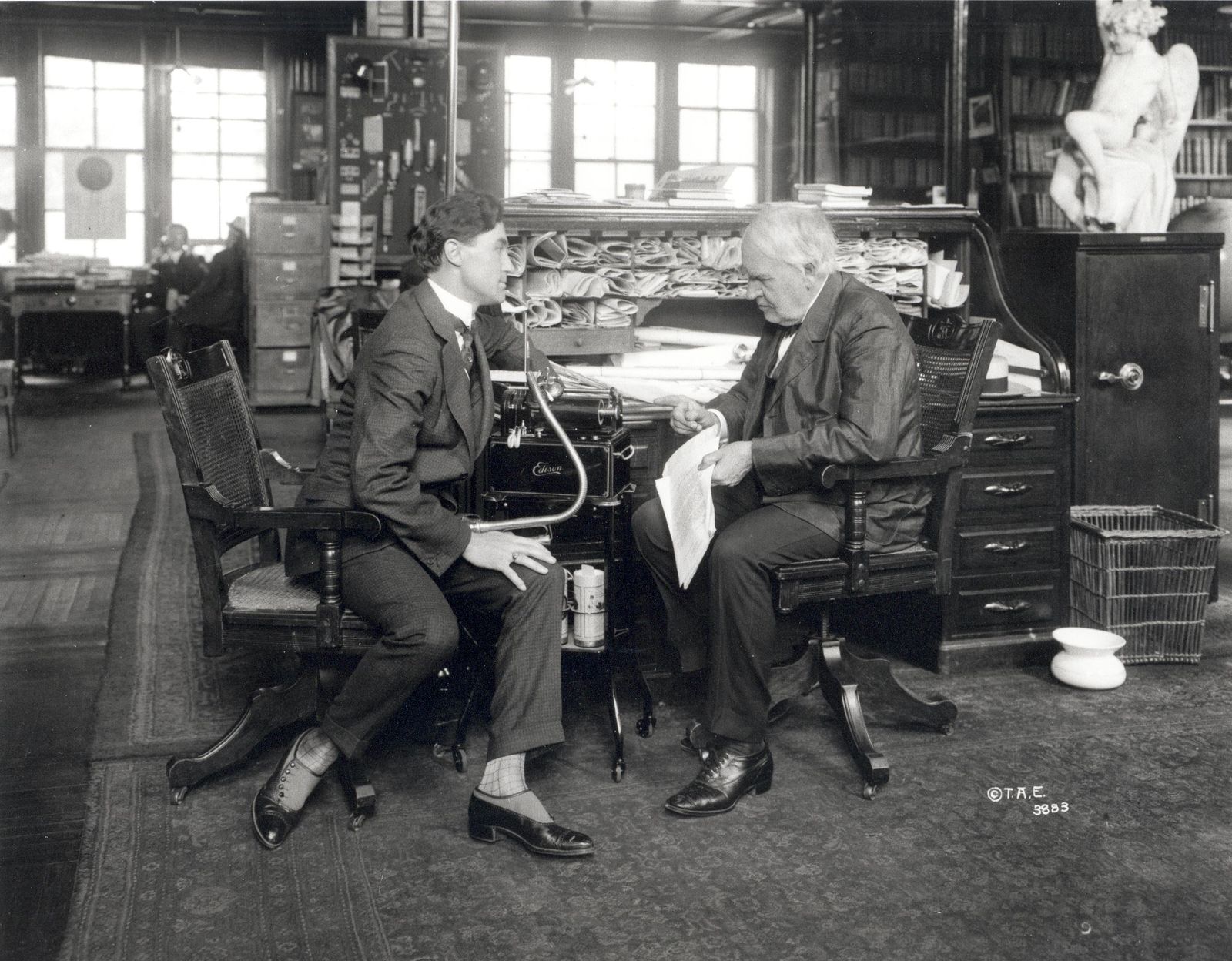

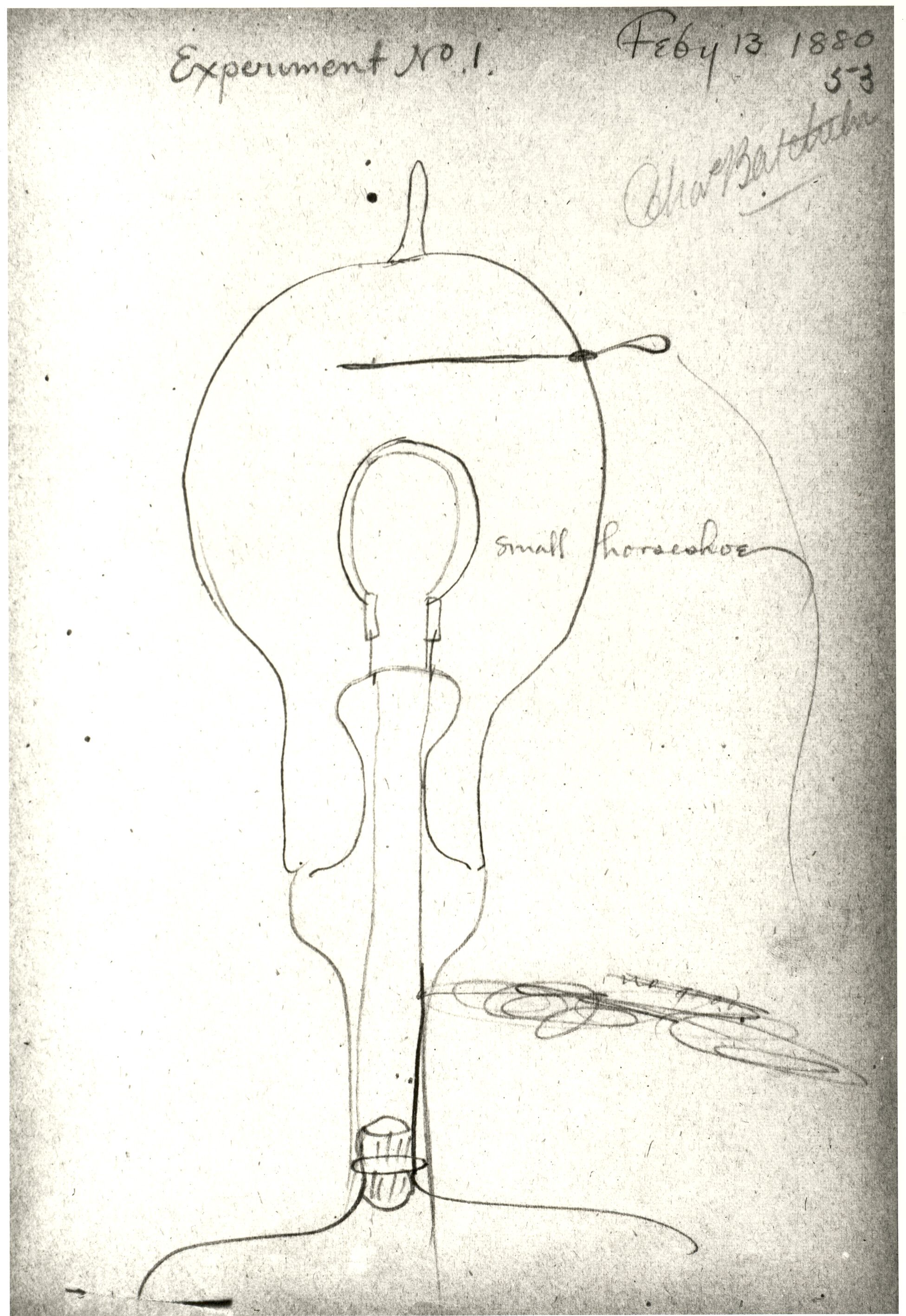

After moving to New York, he began to conceive of a company as an idea factory, keeping track of time he spent developing an idea—hearing-impaired Edison invented the phonograph using Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone technology and he first imagined the electric light in three quick notebook sketches—earning money from investors such as JP Morgan.

As Sterling North observes in his book, Young Thomas Edison:

“From ‘rags to riches’ in three days is quite a success story even for a genius such as Edison. But the deeper meaning was that for years he had been preparing for just such a moment.”

When the stock market crashed, North writes, “what few dollars [Edison] had saved had not been risked in…wild speculation. After a few months Edison and Franklin L. Pope, a highly intelligent telegraph engineer, founded a [business] of their own called Pope, Edison and Co., with J. N. Ashley as a third and silent partner. This was the first firm of electrical engineers ever established.”

Thomas Edison was rarely idle. Striking a balance of making money in lighting while testing and creating inventions in a kind of studio proved to be a challenge for young Edison. But he succeeded in building several lighting companies and eventually sold most of his businesses to a corporation which became the General Electric Company.

Afterwards, according to North, Edison merely sought a good laboratory and time to do his research and inventing. In lush green, peaceful hills—New Jersey’s Orange Mountains—Edison labored night and day in his laboratory. He punched a time clock as did his employees. But “he more than doubled their average work week, sometimes devoting as much as 116 hours between Sunday and Sunday.

Author Edwin Locke writes in The Prime Movers that “Edison is most remembered for his invention of the electric lightbulb…But [h]e envisioned an entire electrical system to go with the bulb…[including] a central power station, insulated wiring, individually controlled lights wired in parallel, meters to measure electrical consumption, and the total cost competitive with natural gas lighting. Edison had to invent, in addition to the lightbulb, the dynamos that would power the stations, the method of wiring and insulation, meters, light fixtures, and fuses. These inventions were made in his laboratory in conjunction with the research on lightbulbs.